Look, up in the sky! It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s Superman! Since his creation by Siegel and Schuster in 1933 and his debut in Action Comics in 1938, Superman has become the most widely-known superhero of all, and possibly the world’s best-known fictional character. Along the way, he has been interpreted in many ways by different writers, from the rough socialist crusader of his early Golden Age appearances, to the Silver Age’s protector of “Truth, Justice, and the American Way’’, to the “big blue Boy Scout” of the modern era and the conflicted alien of the recent movies. Beyond these changes, there have been many “Elseworlds” takes on Superman, stories that place a different version of Superman in another setting, like the Old West or Feudal Japan. In most such stories, one thing that remains unchanged about Superman is his uncommon decency and humanity.

Which brings us to the subject of this review, “What a Difference a Shade Makes”, by Saab Lofton. In this independent Elseworlds story, a dusky-skinned Kal-El is sent from doomed Krypton to Earth, where he will be raised by the white Kents, who do their best, but are unable to love this son quite the way they were able to love the light-skinned Clark we’re all familiar with. The story details how this and other problems he faces due to racism in Smallville and beyond lead Kal-El to become a very different Superman, though no less a hero.

Lofton explains in a non-fiction piece associated with the story that he was inspired by twentieth-century journalist Stetson Kennedy’s infiltration of the KKK, which provided the material for Clan of the Fiery Cross, a story arc on the Superman radio serial in which the threatening mystique of the KKK was demolished, and their secret codes and rituals exposed to the nationwide radio audience. Lofton’s goal for this story is to “finish what that 1946 radio serial started and defeat white supremacy once and for all” by reaching a white audience as wide as the Clan of the Fiery Cross serial.

It’s a tall order. For one thing, Lofton doesn’t have the promotional resources of DC Comics, nor the homogeneity of the 1946 media landscape on his side. Technically, WADSM is fanfic, though there needs to be an alternate term for fanfic by professional writers, such as this, or Peter Watts’ acclaimed “The Things”. And fanfic has a tough row to hoe in finding an audience beyond fannish circles, partly due to legal hurdles on its distribution. To reach its one million readers, WADSM needs to reach the mainstream.

Lofton’s goal is also a tall order because white supremacy seems to be on an ascending trajectory in the US right now. As I write this, the top news stories are of two black men needlessly killed by white police, in different states, on or around the same day. White supremacist organizations demonstrate freely and with the protection of the police, and the Republican nominee for president has declined to repudiate his endorsement by white nationalist leaders. But maybe it’s not as strong as it looks. Maybe we’re seeing the desperate vigor of an ideology that knows it is dying. If so, maybe WADSM is the kick needed to put it down.

So all that said, how is the story?

It’s told as an origin story, mainly as a series of vignettes, spanning the time from his lifeboat’s launch from Krypton to his first meeting with Lois Lane. The path leading there is not quite as straight as “farm boy discovers his amazing powers and moves to the big city to use them for good”. Baby Kal-El is found by the white Kents, who, inspired(?) by Webster and Diff’rent Strokes, choose to adopt the ebony toddler they find in the crashed space capsule. Though they try to see him as their own, they are not able to overcome the social conditioning that makes them see him as different, and lesser, despite his very evident superiority. In a key passage, the Kents repeatedly impress upon young Clark, when they catch him floating over his bed after dreams of flight, that for a man to fly like an angel would be blasphemous, a lesson that sticks with him even after he leaves the Kents.

And leave, he does, after withstanding years of passive-aggressive comments from the people of Smallville, and, finally after being spurned by cheerleader Lana Lang (because, she insists, while she’s not racist, she has to please her “conservative” family)1, being told the truth of his birth by the Kents, and putting a violent end to a KKK cross-burning in his own yard. Not flying, but leaping as if to clear a tall building in a single bound. Unlike the regretful way we see canon Clark leaving his family, called away from his small town to the big city by a big destiny, but with plans to return often, this Kal-El (“Clark is my slave name!”) is glad to kick the dust of Smallville off his Doc Martens.

After this, we get a bit of an interlude telling how Kal-El gradually became known as a semi-fugitive protector of the downtrodden – not merely blacks, but Muslims, homosexuals, women and anyone else threatened by the more powerful. His uniform in this phase of his career recalls the costume of Superman’s early years as imagined by Grant Morrison in the New 52 reboot of Action Comics – work boots, blue jeans, and T-shirt with the S-shield. And both Morrison’s work and Lofton’s recall the Superman of the Golden Age of Comics, when he was a clearly socialist crusader.

This period ends when Kal-El, performing superhuman feats of relief work in Haiti after Hurricane Jeanne, is confronted with the fact that his limited scope of intervention in earthly society is not doing all he could do. This is a direct confrontation with a common theme in DC comics – the fact that were the godlike heroes to do everything in their power to help people, they would have to replace the world’s corrupt and/or ineffective governments, in effect ruling the world. In canon, the Justice League specifically rejects this burden, choosing to let humanity chart its own course, and only intervening to stop disasters, extraterrestrial incursions, and criminal acts.

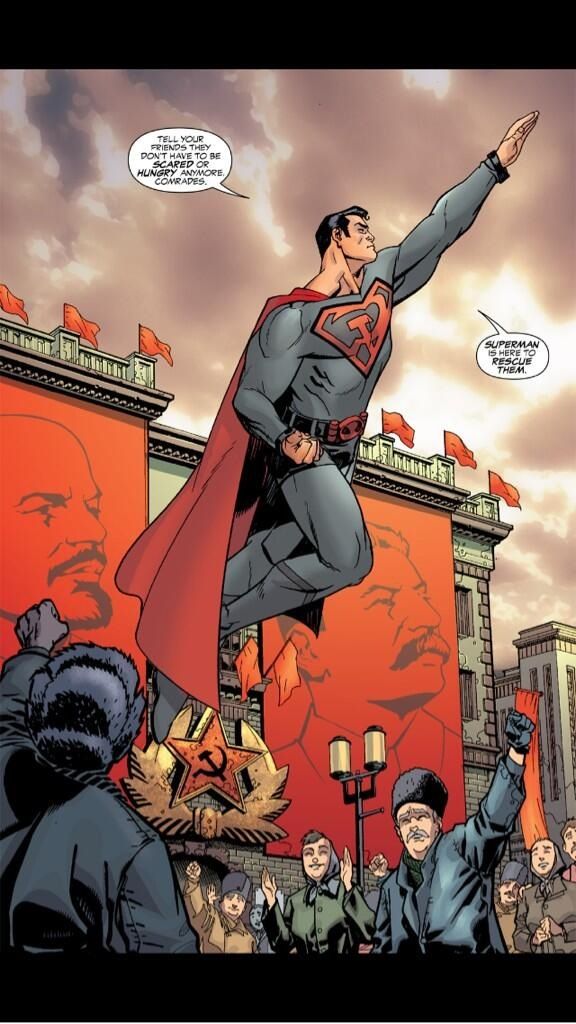

In Elseworlds, this has not always been the case. For example, in the long-running video game spinoff Injustice, Superman is moved by the death of his family at the hands of the Joker to murder the villain and take over the world. But perhaps more pertinent to Lofton’s story is the acclaimed Elseworlds graphic novel, Mark Millar’s Superman: Red Son. Raised on a Ukrainian collective farm, Kal-El becomes “the Champion of the common worker who fights a never-ending battle for Stalin, socialism, and the international expansion of the Warsaw Pact.” After Stalin’s death, Superman initially declines the leadership of the Party, but faced with seeing a childhood friend in a Moscow bread line, he changes his mind, and decides that he can save anyone, and that there’s no reason he shouldn’t.

WADSM Superman comes to the same conclusion as the Soviet Superman – that his power and knowledge would enable him to create a utopia, and that this is the most effective use of his time and abilities. Although originally planning to save Haiti, he instead chooses to build New Krypton in the Congo, so that the sale of coltan can fund the social development.

We see New Krypton through the perspective of reporter Lois Lane, who comes to the Congo to cover the new benevolent dictatorship. We don’t get a full picture of New Kryptonian society, but technologically, they appear to be based on sustainability (solar power, industrial hemp, biodiesel). Culturally, freedom of speech is protected, even for enemies of the state, but pacifism is enforced for all social movements. Gay marriage and womens’ empowerment are protected. In terms of law enforcement, New Krypton has police, who are armed only with tranquilizer darts, but no prisons. Severe offenses are dealt with by exile or administration of ibogaine, a hallucinogen which renders violent offenders harmless. We do not see much of the economic organization of New Krypton.

Lois Lane is initially very skeptical of Kal-El’s achievements, but is gradually won over by his openness and their growing mutual attraction. Their private interview is interrupted by an attack by Metallo, sent by General Sam Lane to enact regime change and restore the low-wage tantalum market, and so we get the one supervillain fight of the story. I won’t spoil the thrilling conclusion of the story, except to note that it moves forward the themes of the story as well as the plot.

What a Difference a Shade Makes is not the first story about a black Superman, but it is distinctly different from its predecessors. In the Silver Age, Krypton was shown to have had an island continent, Vathlo, inhabited by a technologically advanced civilization of black Kryptonians, but no black Kal-El. In and around the Crisis on Infinite Earths (1985-85), two black versions of Superman were shown in the multiverse. First was the Superman of Earth-D, a world similar to the main DC universe, Earth-One, but where the heroes were more ethnically diverse. The second was the extravagantly Afroed Sunshine Superman of Dreamworld, a psychedelic/hippie flavored universe. Neither was a major character.

Post-Flashpoint, there have been two black Supermen, both of which are moderately significant recurring characters. Kalel of Earth-23 actually first appeared in Final Crisis, but starred in a story arc in post-Flashpoint Action Comics, and in the Multiversity miniseries. As Calvin Ellis, he also serves as the President of the United States. Most of the major superheroes of Earth-23 are black, and Kalel is confirmed to have been born on Vathlo Island. Unlike WADSM Kal-El, Earth-23 Kalel does not appear to have faced notable difficulties due to his color while growing up. He was raised by the loving Ellis family, about whom I was unable to find any information. With a Superman based on Barack Obama, and a Wonder Woman based on Beyoncé, Earth-23 reflects the way modern America would like to see itself, a liberal, postracial society where our black heroes absolve us of any responsibility for our structural racism.

The second Superman of post-Flashpoint Earth-2, Val-Zod, is in some ways more interesting. A childhood friend of Kara Zor-El (Power Girl), Val-Zod was raised mainly by the systems of his space capsule, and upon arriving on Earth-2 as a young adult, was kept in seclusion with limited access to sunlight by Terry Sloan (of Earth-3, it’s complicated). Based on his belief that violence is the stupidest solution to any problem, Val-Zod is a pacifist. He will rescue people from danger, and put his near-invulnerable body in harm’s way for others, he will not use force against any sentient being. This is a very significant deviation from the norm in superhero comics, where most problems are solved by punching them in the face, and especially so given that he has taken up the mantle of Superman. In contrast to the previous black Supermen, who are not political in any sense except inasmuch as their blackness in mainstream media is inherently political, Val-Zod is both black and explicitly political. However, it’s not clear how Val-Zod’s blackness relates to his politics. His upbringing was not racialized in the way that WADSM Superman’s was, being mostly isolated from humans and their prejudices. If anything, his philosophy appears to be shaped by his alienness, rather than his blackness, something that is explicitly rejected in WADSM.

So while a black Superman is not new, a Superman who is significantly shaped by his blackness is. This is, in my opinion, the main and significant contribution of What a Difference a Shade Makes, and one that could not, at this time, be made in a work oficially released by DC Comics. After the election of Barack Obama, and before Ferguson, the story of Super-President Calvin Ellis was a tellable story. It didn’t threaten the social order (i.e., white supremacist capitalist patriarchy), because it presents the liberal picture of an assimilated black hero who can work within the system, and, indeed, administer it. It is interesting to note the congruence between Obama’s “Hope” campaign slogan and the interpretation of the crest of the House of El as meaning “Hope”.2

“What a Difference a Shade Makes” deconstructs this story, pointing out the shortcomings of even well-meaning whites, and explicitly making the point that even a non-human alien that “fits the description” will be coded as black by the system of white supremacy.3 Kal-El is shaped by his trials and upbringing, but also by his character, which is substantially the same as the Superman we all know. This is the way in which WADSM most strongly resembles Superman: Red Son; regardless of where his path leads him, Superman is a hero.

Ultimately, “What a Difference a Shade Makes” succeeds as a Superman story and as a challenge to white supremacy, clearly distinguishing itself from its canon forebears through its radicalism and its cultural realism. Whether it will be successful as a political action ultimately depends on its readers.

-

Note that in the current DC continuity, mechanical engineer Lana Lang is dating scientist John Henry Irons, aka Steel, who is black. So it goes. ↩︎

-

The 2015 Supergirl TV series describes the crest of El as meaning “Stronger Together”, which has apparently been picked up as a campaign slogan by Hillary Clinton. The first time as tragedy, the second as farce. ↩︎

-

I’m reminded at this point of the awkwardness of language in the media and fan-media regarding Tuvok, the black Vulcan Starfleet Officer on Star Trek: Voyager. He was frequently referred to as “African-American”, despite the character not being American, not being of African descent, nor, indeed, being Human. ↩︎